This is not an excuse to shut the Film Council

October 7, 2010 - leave a comment

It’s a tough world for the indie filmmaker who makes a movie that doesn’t fit a recognised genre. Low budget, experimental films are not appealing fodder for indie distributors though I believe one positive force was the UKFC and their willingness to take risks in the films that they helped release.

With that risk comes the inevitable high percentage of failure, though the concept of micro budget filmmaking embraces this. The box office rewards are potentially so rich that even if your conversion rate is low, spreading the risk across a number of low budget films pays more dividends than putting all your eggs in one basket. The problem is that as a public body, the number of failures makes you a sitting duck for the popular press who ignore the bigger picture.

It’s a situation that is typified up by our first project with them back in 2003. This Is Not A Love Song was a low budget thriller shot on DV directed by Bille Eltringham and written by Simon Beaufoy (known previously for The Full Monty and subsequently for Slumdog Millionaire).

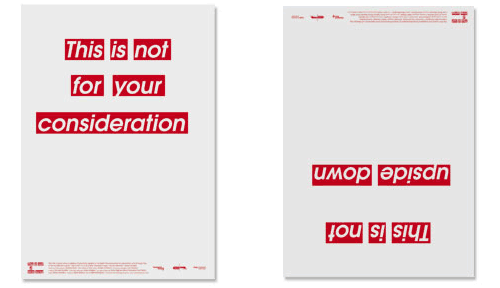

We’d got involved at sales stage, with my business partner Franki devising a Barbara Kruger-inspired print campaign for Cannes and Edinburgh. It was memorable for two reasons; firstly getting to work with and meet artist Dinos Chapman (and in particular one alcohol-fuelled night that randomly involved Uri Geller) and secondly Franki and I having to work through the night hand-finishing 2,000 posters on my kitchen floor (having come up with an ambitious concept way beyond the budget of an indie film) – I remember our ashen faces at the break of dawn, partially due to lack of sleep though mostly down to the large amounts of Spray Mount we’d passively inhaled.

Sadly, the festivals failed to attract a distributor though later in the year the UKFC, who had partially funded the production, hatched an ambitious plan for the film’s distribution. It was to be the World’s first simultaneous online and theatrical release of a film. What better way to put the British Film Industry and this little low budget feature on the map than attempt something that not even Hollywood had done?

Put us on the map it did. And how.

The UKFC acted as the distributors, working with Soda Pictures who managed the theatrical side of the release. We built the website that fronted the download, continuing the style developed for the print campaign (which we still keep online for posterity).

Another company were handling the back end delivery mechanism. In an early meeting with them, they mentioned the decision to offer the download and stream in Windows Media format only. Back then, due to the digital rights management (DRM) that Windows Media offered, it was the only real option. But it restricted who could watch the film. It excluded Mac users who although only accounted for 3% of Internet usage overall, represented a much bigger slice of our target audience (perhaps 20-25%). But, as it turned out, much more damagingly for us, it also restricted Linux users. Although a much smaller percentage again (perhaps less than 1%), it included a number of passionate advocates of open source software who hated the notion of DRM and in particular, Microsoft.

So to the day of release. On Friday September 5 2003 at precisely 6pm the film would be be available to watch online, download or to view at your local arts cinema. The media had loved the story and gave it coverage on a par with a major Hollywood release. The BBC ran the story through the day across their channels (there’s nothing like hourly radio bulletins counting down to motivate you to hit a deadline) and it wasn’t long before international channels starting picking up the story. The film was for UK release only (technically enforced by geo-restricting to UK IP addresses) but that didn’t matter – it had caught the imagination of the World’s entertainment media.

Alas, it also attracted a less well-meaning audience. In the afternoon, the story appeared on slashdot, a site primarily for the Linux and open source communities. They focused on the fact that the film was not available to Linux users. In fact the hoards who read the story and commented furiously, skimmed over much of the important detail – that it was a UK-only release (so they couldnt have watched it anyway as most were in North America) and that it was a small, low budget British indie movie. In their minds, they assumed only Hollywood could be behind a bold venture of this scale and this was therefore Hollywood and Microsoft in cahoots building the model of all future film release. This was the beginning of a bad new world where all movies released online would be Microsoft DRM-controlled. They had to disrupt this experiment.

Nervously and with huge anticipation, the switch was flicked at 6pm. Almost immediately things started to go wrong. The site stopped responding. The backend guys had been beefing up the architecture through the day due to all the press attention though nothing could have prepared us for what happened. For the next few hours waves of denial of service (DoS) attacks launched from across North America rained down on our little site. It was the beginning of a difficult weekend. The tech guys worked hard to shift the points of attack whilst we helped fend off the press. At one point in the middle of the night I got a call from US news channel CNET who’d tracked me down via the registration of the sites domain asking for details of what had gone wrong. We put up a passionate plea from the producer explaining that this was just a small film, that we weren’t funded by Microsoft or Hollywood and that we didn’t hate Macs or Linux. But it was too late.

The decision was made over the weekend to pull the site whilst the tech guys worked on making the system more robust. Frankly, though, even the might of Google and Microsoft have crumbled when the subject of the zombie hoards of a DoS attack.

When it came back several days later, the hoards had gone, but so too had the audience and the press attention, content with their conclusion that the experiment had failed.

But for one glorious day, leading up to the launch, a film that had been overlooked by distributors was making headlines world wide. Many journalists reviewed the film who otherwise would never have seen it and as a result, opened the film up to an audience.

Seven years on and the launch this week of Google TV and a revised Apple TV endorses that online distribution will become a major, if not the major, distribution channel of film. What no one can take away is that it was a low budget, independent British feature that set a major milestone on that path.